Key Factors in Improving the Quality of Education (By: Muchlas Samani)

Efforts to improve the quality of education in Indonesia have been ongoing for a long time. Various programs, projects, and breakthroughs have been tried, whether they are regional initiatives, national initiatives, assistance from foreign experts, or educational institution managers. However, the results have not been encouraging. Data from the National Examination (which will soon be replaced by the Minimum Competency Assessment), PISA results, and several other data show that the quality of our education is still not satisfactory.

The question arises, what is wrong with these various efforts? Have these efforts not addressed the main problems of our education? Using Pareto’s theory, have these efforts not touched on the critical factors of education in Indonesia? In Surabaya language, have these efforts not reached the “core”? Or is the approach wrong? Or are we not serious enough in our efforts? Or, or, or other reasons. This short article is not intended to discuss the reasons mentioned above, but to share the results of an analysis of our school situation, with the hope of providing a perspective based on research data.

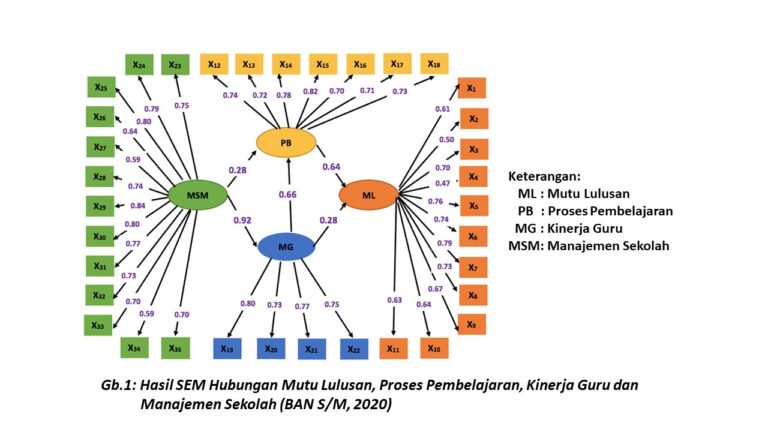

The National Accreditation Board for Schools/Madrasahs has just conducted a trial of its new accreditation instrument. The instrument is indeed new, but the analysis results show very good validity and reliability. In Figure 1, it can be seen that the intercorrelation of items (X1-X11) with their parent variable (ML=graduate quality), items (X12-X18) with their parent variable (PB=learning process), items (X19-X22) with their parent variable (MG=teacher performance), and items (X23-X35) with their parent variable (MSM=school management) are quite good. Thus, the results are strong enough to be used as conclusions.

Figure 1 also shows the results of SEM analysis processed from more than a hundred schools. From the figure, it can be seen that 64% of graduate quality can be explained by the learning process that occurs. Meanwhile, 66% of the learning process can be explained by teacher performance. And 92% of teacher performance can be explained by school management. If these figures are examined, all are above 60%, which can simply be interpreted that other factors are certainly smaller.

If graduate quality is interpreted as the main indicator of education quality, then the SEM results can be summarized as follows. Education quality is strongly influenced by the quality of the learning process that occurs in schools, while the quality of the learning process is influenced by teacher performance, and teacher performance is influenced by school management. Using Pareto’s theory, improving school management and teacher performance becomes the main key in improving education quality.

If graduate quality is interpreted as the main indicator of education quality, then the SEM results can be summarized as follows. Education quality is strongly influenced by the quality of the learning process that occurs in schools, while the quality of the learning process is influenced by teacher performance, and teacher performance is influenced by school management. Using Pareto’s theory, improving school management and teacher performance becomes the main key in improving education quality.

These findings are in line with Abu Dohuo’s (199) findings that student learning outcomes are the result of learning innovations carried out by teachers. To innovate, three conditions are required: teachers must have competence and commitment to innovate to improve student learning outcomes. Well, teacher work commitment is greatly influenced by the work climate, and the work climate is the result of school management.

Do these findings also apply to higher education? So far, I have not read any research like this in the context of higher education. However, if we read articles about outcome-based education, such as the article by Eldeeb and Shatakumari (2013) titled “Outcome Based Education: Trend Review,” and about outcome-based accreditation, such as Harmanani (2017) titled “An Outcome Based Assessment Process for Accrediting Computer Programmes,” it seems to also apply to higher education. It would certainly be very good if there were research replicating the above research in the context of higher education in Indonesia.